Robert Hurst and Nancy Hudson, two Yawn Publishing authors, are interviewed about their recently released books.

Author: admin

THE DAY THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION CAME TO BAY COUNTY

This is the first of a two part history on the Revolutionary War and an Indian Trading Path

October 1, 1778 to be exact. That was the day that British Captain David Holms, his surveyor and cartographer Joseph Purcell, and five Creek warriors marched down the Ekanachattee Trading Path and onto what was to become Bay County soil on their return to their base in Pensacola.

As we celebrate the day of the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776. We should remember that the American Revolutionary War was raging as a result of our desire to be independent of the British Crown. It is interesting to observe, though very minor, the events that resulted in the above march into our area.

Floridians, though loyal British subjects, did participate in the war. There were incursions into each others domain by both British and “Rebel” subjects.

Under General Robert Howe, a group of Continentals and Georgia and Carolina militias advanced into East Florida. Their goal apparently was to occupy St. Augustine, East Florida’s provincial capital. They defeated the combined British and Seminole forces at St. Simons and St. Marys Rivers. British Governor Patrick Tonyn, alarmed, sent out urgent appeals to John Stuart, Indian Agent, who was at the time in Pensacola, to send help, especially from the Indians of West Florida and northwards. Help was slow in coming. The Americans were right on the heels of the retreating British force, both of which ran right into an awaiting British force along the Nassau River. On July 14,1778 in a chaotic Battle of Alligator Creek Bridge, where Red Coats and Rebels were confused with each other as to whom the enemy were, the British finally turned back the American force.

Meanwhile, back in Pensacola, an expedition to aid the British of East Florida was organized. On July 14, 1778, a force of ten Whites and twenty-two Upper Creek Indians under Captain David Holms set out on a land journey to St. Augustine. Among the Whites were Lieutenant Timothy Barnard, Joseph Purcell and John Random.

Captain Holms and Lieutenant Barnard were cousins. Surprisingly their uncle was George Galphin, John Stuart’s rival as the “rebel” commissioner to the Lower Creeks. In 1775 Holmes had been acting agent to the Lower Creeks for Galphin. In the fall of 1777, he and Barnard appear to have defected to the British cause in West Florida. In September, he joined the British Southern Indian Department and before the end of the month, he was delivering “talks” from John Stuart to the Lower Creeks. In 1778 he was appointed extra commissary in the Southern Indian Department and cousin Barnard was an assistant. While it may appear that Holms, as well as Barnard, might be considered traitors for the apparent defection to the British, many of the Florida British, including Governor Tonyn, suspected them of still acting in the interests of the rebels.

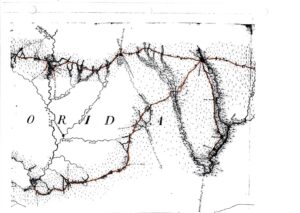

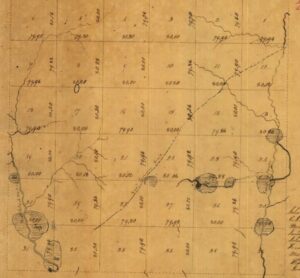

Mapmaker Purcell used this 1778 expedition to record his observations and data for the purpose of preparing a map of the roads and geography. His map “The Road from Pensacola in West Florida to St. Augustine in East Florida” is the only definitive map of the Old Spanish Trail as it existed in the 18th Century. This is the most important contribution that these otherwise minor events produced.

Captain Holms also recorded his observations in a day-by-day journal, which also sheds much light on the conditions in this part of the land. The journal indicates, for example, that the expedition intended to gather Indian reinforcements along the way. By the time they reached St. Augustine on August 29 their force had swollen to approximately 240.

Reading between the lines, the Governor was not pleased to find over 200 Seminoles and Creeks gathered at the walls of his town. This force arrived too late. The Rebels had retreated and the province was at the time out of danger. He spoke to them and told them to return home and to “remain quiet until such time as they heard from him again”. Veiled in perhaps a warning to them, he said that “the great King’s ships were as numerous as the sand on the seashore and his soldiers as numerous as the leaves on the trees”. One of the Indians turned the tables on this observation by noting that “if the Great King’s ships were as numerous as what the Governor had told them, he did not imagine but they were sufficient to subdue the Americans without the help of the red people“.

Governor Tonyn on September 8 complained to Stuart that “Holms and Barnard arrived too late to help East Florida. Their loyalty in questionable. We could and should have had more Indians here”.

Now here is where the future Bay County territory plays a minor part in the events occurring in 1778. On the return of the army to Pensacola, Holms, Purcell and five Indians chose the shorter route, and between September 30 and October 2, marched down the 100 mile Ekanachattee Trading Path, where at the Anglo-Creek Trading Store at the mouth of the Choctawhatchee River, boarded a boat for Pensacola.

Actual participants in the American Revolution not only tread on Bay County soil, but also on Jackson, Washington and Walton County’s as well. So if our counties ever wished to form a Continental Line or Loyalist reenactment group, there would be an actual event that happened here with a cast of Red Coats and Indians!

For more on the history of Bay County, visit the History Museum of Bay County, open 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., Tues., Thurs., and Sat., at 133 Harrison Av.

Next week read the second in a two part series: “The Earliest County Road and Court Martial Lake”.

Robert Hurst, author of The Spanish Road, Travels along Florida’s Royal Road, El Camino Real. Floridasspanishtrail.com

THE EARLIEST COUNTY ROAD AND COURT MARTIAL LAKE

This is the second in a two part series on the Revolutionary War and an Indian Trading Path.

For many years, Tom Bowen of Chipley and myself, armed with Joseph Purcell’s 1778 “Map of the Road from Pensacola in West Florida to St. Augustine in East Florida”, the early survey maps and field notes, and early aerial photos, traced out this spur trail from Ekanachattee (present Neal’s Landing) on the Chattahoochee River to the Indian Trading Store at the mouth of the Choctawhatchee River. Joseph Purcell called it “The Trading Path from Santa Rosa [Choctawhatchee] Bay to Ekanachattee”.This was the earliest recorded road, more correctly path, in our area. We photo-documented the remaining trail. We, not surprisingly, found that as with most early trails, the route chosen was usually the path of least resistance. As a matter of fact, the basin divide that separates the Choctahatchee and St. Andrews basins in Bay County follows the same route as the old path.

The county sections that hold the trail are the Steel Field/Seminole Hills, Pine Log State Forest and Court Martial Lake areas. There are still surviving names and bridge pilings that are left. Ninemile and Tenmile Branches are exactly nine and ten miles along the path from the Indian Store. Moving east, a traveler along the road would approach his first hill, Seminole Hill, once with an elevation of seventy feet. Now the Bay County Land Fill sits atop it and the elevation has been reduced to twenty to thirty feet. Could there be a connection with this Seminole trading path that crossed it? Crossing the upper reaches of Otter Creek and advancing northeast and passing Gunlock Cemetery in Pine Log State Forest, at the crossing of Little Crooked Creek are the remains of wooden bridge pilings. Going east, the old path crossed present State Road 79 and along Pine Log’s Carbody Road.

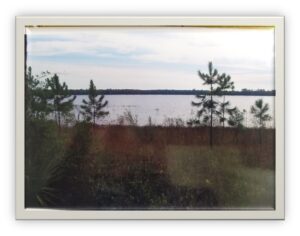

The traveler going northeast would gradually ascend into the sand hills. He would encounter on its west, then north sides, Court Marshall Lake. In 1778, mapmaker Purcell called it “The Southernmost Great Pond”, obviously unaware of Lakes Merial and White Western. The early 1831 land surveys label it “Bear Pond”. The name Court Martial Lake seems to have originated out of the belief that General Andrew Jackson in his 1818 march across North Florida, executed after a military trial, the British subjects, Alexander Arbuthnot and officer Robert C. Ambrister. The two had been charged with inciting the Indians to war against the United States. Local author and News Herald writer Harold Bell in his book Glimpses of the Panhandle related of a visit to the lake with local resident Ed Banks. On the northwest side of the lake, he describes “an elevated area which is plainly marked out”. He identified this as the campsite of Jackson. Approximately a mile from the site, Bell discovered a corduroy road that he may rightly identify with the Military or Federal Road built in the early 1820’s. It was also the Ekanachattee Trading Path that the Military/Federal Road picked up and used for several miles on its east northeast journey.

There is no documentary evidence that General Jackson ever set foot even near Court Martial Lake. Arbuthnot and Ambrister were tried and executed near St. Marks. Jackson’s march across northwest Florida to Pensacola in 1818 took him much farther north. The closest he ever got to Court Martial Lake was in the Graceville and State Road 2 area, near the Alabama State line.

So the question remains, how did the lake get associated with Andrew Jackson? It is likely that the close proximity of the 1824 Military Road was somehow associated with him. Indeed, the same road in the Gulf Shores and Eglin Air Force Base areas are often referred to as “Jackson’s Trail”. As for the campsite, it is interesting to observe that the distance from the Indian Store at Choctawhatchee to Court Martial Lake is approximately 24.25 miles. This is about the distance that a trading party could travel in a day. The campsite that Banks recollected as being Jackson’s stop, might have been confused with a customary Indian and trader campsite along the Trading Path, and there is indeed an elevated ground on the northwest side of the lake that the Trading Path crosses.

From Court Martial Lake the traveler began a northeasterly ascent into the Sand Hills proper, passing south of Crystal Lake and into present Washington County.

The significance of this trail must first be put in historical context. Before the Revolution, most trade with the Indians filtered through Charleston, but the war disrupted this trade. Pensacola became a major outlet. Goods now flowed from the east to Pensacola. The Chattahoochee/Apalachicola and Choctawhatchee River systems became important highways. One of the routes involved the Indian Store at the mouth of the Choctawhatchee. Maintained by a Mr. Gough, it was probably owned by the Scotsman, John Miler. From the store goods could flow down a natural inland waterway to Pensacola by British schooners and Indian canoes. The overland route to the east would have been along this 100 mile Ekanachattee Trading Path, a segment herein described. The white traders traveled with packhorses that could average about 25 miles per day. These animals proceeded single file, none of them bridled, along the narrow path. Strings of sleigh bells and hawk bells adorned them so that they would not get lost when turned loose at night. European goods that were traded to the Indians consisted of blankets, boots, guns, check shirts, hatchets, calico, gartering, “nonsopretties”, silk ribbon, broad hoes, rum, barley, corn, small beads, bullets, flints, gun powder, looking glasses, thick saddler’s laces, small black duffels, broad ribbons, paint “of which the Red People are very fond”, and knives. From the Indians, the British desired deer skins. So large was this trade that it is said the Indians hunted the deer almost to extinction.

With the coming of the Americans in the 1820’s, settlement patterns changed. Instead of the Indian Store, there was Point Washington. Instead of the Indian village Ekanachattee, there was Marianna and Port Jackson. The trail, though altered, continued in use no doubt through much of the 19th Century. It still survives today as primitive trails and logging roads in many parts of our county.

For more on the history of Bay County, please visit the History Museum of Bay County, 133 Harrison Avenue. Open hours are Tuesday, Thursday and Friday, 10 a.m. to 1 p.m.

Robert Hurst, author of The Spanish Road, Travels along Florida’s Royal Road, El Camino Real. Thespanishtrail.com

Check out this interview about Florida’s Spanish Trail

Article in the Panama City News Herald

Check out this recent article:

BICENTENNIAL ANNIVERSARY OF ANDREW JACKSON’S MARCH DOWN THE JACKSON TRAIL

Have you ever hiked a Native American trading path? Or the Old Spanish Trail? Or General Jackson’s Trail? Or in the footsteps of a Revolutionary band of soldiers? Well there is a part of the Florida Trail that is at least 230 years old and embodies all of the above! An event and anniversary recognized its history and recreational asset.

BICENTENNIAL ANNIVERSARY OF ANDREW JACKSON’S MARCH DOWN THE JACKSON TRAIL

BY ROBERT HURST

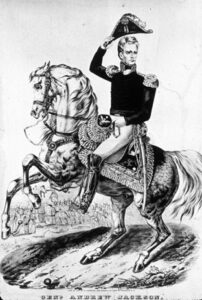

ANDREW JACKSON

“After a fatiguing, tedious and circuitous march of twelve days, misled by the ignorance of our pilots and exposed to the severest of privations, we finally reached and effected a passage over the Escambia.” General Andrew Jackson to John C. Calhoun, Secretary of War, June 2, 1818.

This march on Pensacola was by an army of approximately 1200 men, wagons and heavy artillery across West Florida during the final stages of the First Seminole War in Florida. While campaigning in Florida, Jackson had received word that the Spanish government in Pensacola were harboring 450 Indians, who were alleged to have plundered and murdered Americans. In addition, the Spanish had seized the schooner Arrelia that was taking American supplies to Fort Crawford. Jackson reacted by marching west across the relatively unknown land of West Florida and eventually occupying Spanish controlled Pensacola. This act exposed the weakness of the Spanish and resulted in Spain ceding the Floridas to the U.S. in the 1819 Adams-Onis Treaty.

As they moved along the Red Ground Path and across the Choctawhatchee River, their guides became lost. The Red Ground Path was probably named for a tribe of Creek Indians called the Red Grounds or Ekanachattees, who lived along the west bank of the Chattahochee River and in Florida territory.

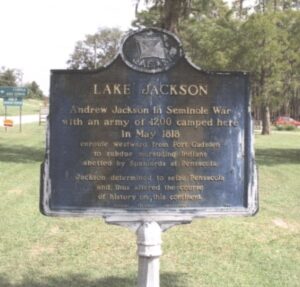

Probably on May 18 the army camped at David’s Lake, which thereafter became Lake Jackson. Florida and Alabama share this border lake. On the north side, Alabama erected an historic marker recognizing the alleged campsite of the invading army.

Lake Jackson Historical Marker erected in 1966 by the Alabama Historical Association, Florala, AL. Courtesy Waymarking.com.

LOWER CREEK TRADING PATH

It wasn’t until somewhere between David’s Lake and the Yellow River that they found the well-traveled trail called the Lower Creek Trading Path. [i]

“The Path between Mounty Pleasant [Floridatown] and the Fork of the Lower Creek Trading Path is plain and well trod,…” Joseph Purcell, Map of the Road from Pensacola in West Florida and St. Augustine in East Florida, 1778.

Jackson’s troops were not the first army to tread on the path. In 1778 a small detachment of British Soldiers led by Captain David Holmes marched from Pensacola on their way to aid the besieged Governor Patrick Tonyn in St Augustine. This was the time of the American Revolution and the Americans were attempting an invasion to take control of St. Augustine. The British had Creek and Seminole allies with them as well as the cartographer, Joseph Purcell, who mapped the road and terrain that he encountered. His work in a virtual unknown area was used by pioneers even into the 1820’s, and is the only definitive map of what we call the Old Spanish Trail, El Camino Real.

Jackson’s troops were not the first army to tread on the path. In 1778 a small detachment of British Soldiers led by Captain David Holmes marched from Pensacola on their way to aid the besieged Governor Patrick Tonyn in St Augustine. This was the time of the American Revolution and the Americans were attempting an invasion to take control of St. Augustine. The British had Creek and Seminole allies with them as well as the cartographer, Joseph Purcell, who mapped the road and terrain that he encountered. His work in a virtual unknown area was used by pioneers even into the 1820’s, and is the only definitive map of what we call the Old Spanish Trail, El Camino Real.

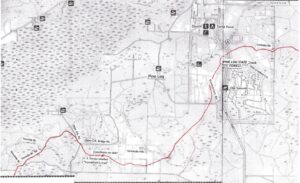

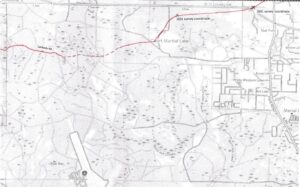

Portion of Joseph Purcell’s 1778 Map of the Road from Pensacola in West Florida to St. Augustine in East Florida showing the Lower Creek Trading Path and the western terminus of the Red Ground Path (upper right corner). The southwest terminus of the Path is labelled “Mount Pleasant”, present Floridatown. Courtesy National Archives, London, U.K.

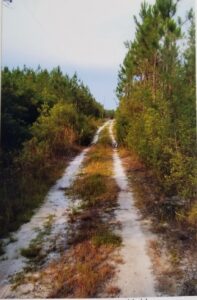

Trace of General Jackson’s Trail east of Yellow River

Present day Yellow River Baptist Church Road on the footprint of the Jackson Trail.

This trail was the major commercial land route from Pensacola to the homeland of the Lower Creeks in Georgia. It’s first 79 ¾ miles however were also used to travel east. At a point north of present Lockhart, Alabama, the traveler, who had so far been traveling northeast, could fork to his right and continue east along the Red Ground Path and could by connecting with other trails eventually reach St. Augustine.

Primitive Trail, thought to be on the Jackson Trail, Pace, FL

JACKSON TRAIL

After Jackson’s march down this path, it became known as “Gen’l Jacksons Trail” and then the Jackson Trail. I used to think as I viewed the old 1826 and 1828 survey maps that the designation “Gen’l Jackson” was the surveyors short hand, but I’ve come now to believe that it was simply the Cracker way of rendering phonetically their pronunciation of Jackson’s title.[ii]

1828 U.S. Survey 3N, Range 27N map of Township showing “Gen’l Jacksons Trail”

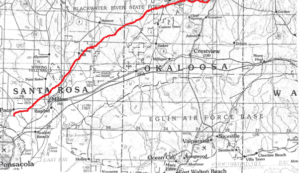

Jackson’s army descended from the “mountains” of Florida – actually hills with an elevation over 300 feet near present Laurel Hill. Here lie the highest elevations in Florida.[iii] Crossing the Yellow River, they followed a 200-250 foot elevated ridge to the Blackwater River.

Portion of I. G. Searcy’s 1829 Map of Florida showing the “Jackson Trail”. Courtesy Library of Congress.

BLACKWATER RIVER STATE FOREST

It was along this ridge and probably around May 19 or 20, 1818, that his army marched into what later became the largest State-owned forest in Florida, the Blackwater River State Forest. Located in Okaloosa and Santa Rosa Counties, and established in 1939, it holds, along with Alabama’s Conecuh National Forest, the largest contiguous longleaf pine/wiregrass communities in the nation. The colorful pitcher plants are interspersed here – all five varieties. These carnivorous plants lure, trap and digest insects. Hills with titi swamps and waterways in the folds dot the landscape. Occasionally a patch of sand pine scrub, a view of farmland and a boardwalk or bridge across a cypress-lined creek will be encountered. Fox squirrels inhabit the forest and are enormous in comparison to the customary gray squirrel.

It was along this ridge and probably around May 19 or 20, 1818, that his army marched into what later became the largest State-owned forest in Florida, the Blackwater River State Forest. Located in Okaloosa and Santa Rosa Counties, and established in 1939, it holds, along with Alabama’s Conecuh National Forest, the largest contiguous longleaf pine/wiregrass communities in the nation. The colorful pitcher plants are interspersed here – all five varieties. These carnivorous plants lure, trap and digest insects. Hills with titi swamps and waterways in the folds dot the landscape. Occasionally a patch of sand pine scrub, a view of farmland and a boardwalk or bridge across a cypress-lined creek will be encountered. Fox squirrels inhabit the forest and are enormous in comparison to the customary gray squirrel.

“Trod by Indians, Redcoats, and Volunteers, Now on the ridge, the lovely pitcher plant rears Overlooking the path Andy Jackson came down To the wary Spaniards at Pensacola town.” Trumpet-leaf Pitcher Plant, Sarracenia flava, Jackson Trail, Blackwater River State Forest, May 9, 2013

There were several waterways that the traveler would encounter on Jackson’s Trail, all tributaries of Blackwater River. Panther Creek, called Mole Branch by Purcell, is described by Young as “twelve feet wide with open banks and sandy bottom.” Next would be the Blackwater River, one of the few shifting sand bottom streams which remains in its natural state. The 18th Century Spanish traveler Don Lorenzo y Ayala called it the Colorado River. Purcell called it Red Clay Creek or Futeechattelagga. Traveling south, next would come the upper reaches of two prongs of Muddy Branch, and then Beaver Creek, perhaps Purcell’s Boggy Cut. At the west boundary of the Forest, the old trail crossed Juniper Creek, Purcell’s Palmetto Creek or Tallahatchee with “…high steep hills on the east and a palmetto flat on the west…” Both Juniper and Blackwater are kayak waterways.

The Lower Creek Trading Path or the Jackson Trail in Okaloosa and Santa Rosa Counties

.

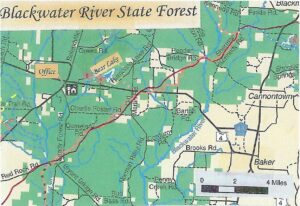

FLORIDA TRAIL-JACKSON TRAIL

In 1970 this historic trail received some recognition by the creation of a hiking trail by the forest rangers. Approximately 20 miles of trail from the Panther Creek-High Bridge Road intersection in the north to the Big Juniper Creek-Red Rock Road intersection in the south roughly follows the old footprint.[iv] The late judge and historian E. W. Carswell of Chipley, Florida claims to have suggested the idea to the Forestry Service. About 100 people attended the ribbon cutting on December 11, 1970. In attendance was Agricultural Commissioner Doyle Conner, Forest Director John Bethea and Judge Carswell. The first group to hike the total length of the trail was Crestview Boy Scout Troop 30. It is maintained by the Western Gate Chapter of the Florida Trail Association. In 1983 it became part of the Florida National Scenic Trail. There are only 11 National Scenic Trails in the nation.

Bob Hurst on the Jackson Trail, Blackwater River State Forest, April 23, 2013

HISTORIC SITES

The hiker might visit a couple of historic sites along the trail. The first would be the site of the Indian then pioneer settlement of Otahite, meaning “damp place”. It was probably located near Peaden Bridge, and on the west side of Blackwater River. In 1880 a new post office was requested for the community. In 1909, the post office was moved about 2 miles to the west. There can be found today the Otahite Cemetery just to the south of the junction of Beaver Creek and State Forest Roads. The Wilkinson, Peaden, Mashburn, Snowden and Turvin families are associated with the community and cemetery.

Crossing into Santa Rosa County and along Cemetery Road is the old Ates Cemetery. The oldest burial that I have found dates to 1891, and the latest 2015. Two of the main families buried there are Ates and Foster.

END OF THE TRAIL

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 spelled the death knoll for the old trading path. Trade with the Creeks ceased, and newer improved roads shortened the distances between the newly created settlements of the white man. The 1824 Federal Road for example improved the travel time across Florida from Pensacola to St. Augustine. Nevertheless parts of the old trail were used even into the present. Small sections of State Highways 2 and 4 and County Road 189, as well as of forest roads High Bridge, Sherman Kennedy, and Peaden Bridge are in its footprint. Thanks to the Florida Trail Association, the old trail has come to life once again. A recreational trail has been created as well as a portion of history preserved, a win for both eco and heritage tourism.

On Saturday May 19th 2018, the Western Gate Chapter of the Florida Trail Association held an approximately 10 mile hike along the Jackson Trail in recognition of the march of Jackson’s army. Among the participants was the Crestview Boy Scout group, observing the first hike on this trail in 1970 by Crestview Troop 30.

Map of a section of Blackwater River State Forest showing the Jackson/Florida National Scenic Trail in orange and blue and the historic Jackson’s Trail/Lower Creek Trading Path in red.

ADDITIONAL PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE JACKSON TRAIL. Courtesy Floridahikes.com.

[i] There were several “Lower Creek Trading Paths” in the southern part of what eventually became the United States.

[ii] Judge E. W. Carswell assumed that this trail was the “Red Ground Trail” as implied by historians Mark F. Boyd and Gerald M. Ponton in their annotations in “Topographic Memoir on East and West Florida with Itineraries of General Jackson’s Army, 1818 by Captain Hugh Young, Corps of Topographical Engineers, USA”, Florida Historical Quarterly XIII, 3 (Jan. 1935), f.n. 62, 157; however Boyd and Ponton readily admit that the trail on Barnard Roman’s Map of 1775 is shown as the “Road to the Upper Creek Nation.” Furthermore Joseph Purcell on his 1778 Map of the Road from Pensacola in West Florida to St. Augustine in East Florida clearly shows the “Red Ground Path” to be an east-west route from the Seminole village of Ekanachettee (Red Ground) to the point of intersection with The Lower Creek Trading Path. Close to this intersection is another intersecting trail called the “Path to the Tukabatchees,” who were the Upper Creeks. The designation Jackson Red Ground Trail therefore is historically inaccurate.

[iii] 12 miles east of Laurel Hill is Britton Hill, the highest natural elevation in Florida (345 feet).

[iv] I estimate that only about 10.5 percent of the Florida Trail is in the footprint of the historic trail. 25.7 percent closely parallels it, and 63.7 percent diverges considerably from the original. The 1826, 1828 and resurvey maps of 1851 recorded coordinates of the trail along section lines. To determine the route between the coordinates involved using early aerial photos from the 1940’s and 1950’s. In most cases, trails or vestiges of trails could be discerned connecting the coordinates. If no signs of trails could be detected, the route of less resistance was used.