This is the first of a two part history on the Revolutionary War and an Indian Trading Path

October 1, 1778 to be exact. That was the day that British Captain David Holms, his surveyor and cartographer Joseph Purcell, and five Creek warriors marched down the Ekanachattee Trading Path and onto what was to become Bay County soil on their return to their base in Pensacola.

As we celebrate the day of the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776. We should remember that the American Revolutionary War was raging as a result of our desire to be independent of the British Crown. It is interesting to observe, though very minor, the events that resulted in the above march into our area.

Floridians, though loyal British subjects, did participate in the war. There were incursions into each others domain by both British and “Rebel” subjects.

Under General Robert Howe, a group of Continentals and Georgia and Carolina militias advanced into East Florida. Their goal apparently was to occupy St. Augustine, East Florida’s provincial capital. They defeated the combined British and Seminole forces at St. Simons and St. Marys Rivers. British Governor Patrick Tonyn, alarmed, sent out urgent appeals to John Stuart, Indian Agent, who was at the time in Pensacola, to send help, especially from the Indians of West Florida and northwards. Help was slow in coming. The Americans were right on the heels of the retreating British force, both of which ran right into an awaiting British force along the Nassau River. On July 14,1778 in a chaotic Battle of Alligator Creek Bridge, where Red Coats and Rebels were confused with each other as to whom the enemy were, the British finally turned back the American force.

Meanwhile, back in Pensacola, an expedition to aid the British of East Florida was organized. On July 14, 1778, a force of ten Whites and twenty-two Upper Creek Indians under Captain David Holms set out on a land journey to St. Augustine. Among the Whites were Lieutenant Timothy Barnard, Joseph Purcell and John Random.

Captain Holms and Lieutenant Barnard were cousins. Surprisingly their uncle was George Galphin, John Stuart’s rival as the “rebel” commissioner to the Lower Creeks. In 1775 Holmes had been acting agent to the Lower Creeks for Galphin. In the fall of 1777, he and Barnard appear to have defected to the British cause in West Florida. In September, he joined the British Southern Indian Department and before the end of the month, he was delivering “talks” from John Stuart to the Lower Creeks. In 1778 he was appointed extra commissary in the Southern Indian Department and cousin Barnard was an assistant. While it may appear that Holms, as well as Barnard, might be considered traitors for the apparent defection to the British, many of the Florida British, including Governor Tonyn, suspected them of still acting in the interests of the rebels.

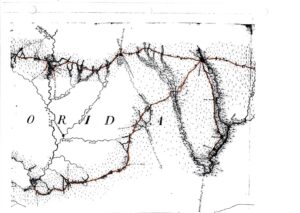

Mapmaker Purcell used this 1778 expedition to record his observations and data for the purpose of preparing a map of the roads and geography. His map “The Road from Pensacola in West Florida to St. Augustine in East Florida” is the only definitive map of the Old Spanish Trail as it existed in the 18th Century. This is the most important contribution that these otherwise minor events produced.

Captain Holms also recorded his observations in a day-by-day journal, which also sheds much light on the conditions in this part of the land. The journal indicates, for example, that the expedition intended to gather Indian reinforcements along the way. By the time they reached St. Augustine on August 29 their force had swollen to approximately 240.

Reading between the lines, the Governor was not pleased to find over 200 Seminoles and Creeks gathered at the walls of his town. This force arrived too late. The Rebels had retreated and the province was at the time out of danger. He spoke to them and told them to return home and to “remain quiet until such time as they heard from him again”. Veiled in perhaps a warning to them, he said that “the great King’s ships were as numerous as the sand on the seashore and his soldiers as numerous as the leaves on the trees”. One of the Indians turned the tables on this observation by noting that “if the Great King’s ships were as numerous as what the Governor had told them, he did not imagine but they were sufficient to subdue the Americans without the help of the red people“.

Governor Tonyn on September 8 complained to Stuart that “Holms and Barnard arrived too late to help East Florida. Their loyalty in questionable. We could and should have had more Indians here”.

Now here is where the future Bay County territory plays a minor part in the events occurring in 1778. On the return of the army to Pensacola, Holms, Purcell and five Indians chose the shorter route, and between September 30 and October 2, marched down the 100 mile Ekanachattee Trading Path, where at the Anglo-Creek Trading Store at the mouth of the Choctawhatchee River, boarded a boat for Pensacola.

Actual participants in the American Revolution not only tread on Bay County soil, but also on Jackson, Washington and Walton County’s as well. So if our counties ever wished to form a Continental Line or Loyalist reenactment group, there would be an actual event that happened here with a cast of Red Coats and Indians!

For more on the history of Bay County, visit the History Museum of Bay County, open 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., Tues., Thurs., and Sat., at 133 Harrison Av.

Next week read the second in a two part series: “The Earliest County Road and Court Martial Lake”.

Robert Hurst, author of The Spanish Road, Travels along Florida’s Royal Road, El Camino Real. Floridasspanishtrail.com

THE EARLIEST COUNTY ROAD AND COURT MARTIAL LAKE

This is the second in a two part series on the Revolutionary War and an Indian Trading Path.

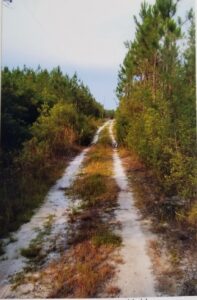

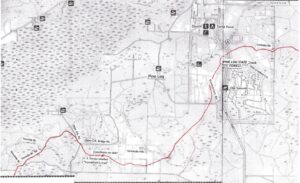

For many years, Tom Bowen of Chipley and myself, armed with Joseph Purcell’s 1778 “Map of the Road from Pensacola in West Florida to St. Augustine in East Florida”, the early survey maps and field notes, and early aerial photos, traced out this spur trail from Ekanachattee (present Neal’s Landing) on the Chattahoochee River to the Indian Trading Store at the mouth of the Choctawhatchee River. Joseph Purcell called it “The Trading Path from Santa Rosa [Choctawhatchee] Bay to Ekanachattee”.This was the earliest recorded road, more correctly path, in our area. We photo-documented the remaining trail. We, not surprisingly, found that as with most early trails, the route chosen was usually the path of least resistance. As a matter of fact, the basin divide that separates the Choctahatchee and St. Andrews basins in Bay County follows the same route as the old path.

The county sections that hold the trail are the Steel Field/Seminole Hills, Pine Log State Forest and Court Martial Lake areas. There are still surviving names and bridge pilings that are left. Ninemile and Tenmile Branches are exactly nine and ten miles along the path from the Indian Store. Moving east, a traveler along the road would approach his first hill, Seminole Hill, once with an elevation of seventy feet. Now the Bay County Land Fill sits atop it and the elevation has been reduced to twenty to thirty feet. Could there be a connection with this Seminole trading path that crossed it? Crossing the upper reaches of Otter Creek and advancing northeast and passing Gunlock Cemetery in Pine Log State Forest, at the crossing of Little Crooked Creek are the remains of wooden bridge pilings. Going east, the old path crossed present State Road 79 and along Pine Log’s Carbody Road.

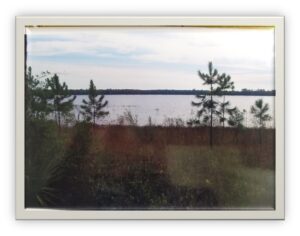

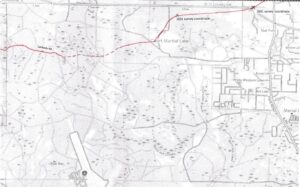

The traveler going northeast would gradually ascend into the sand hills. He would encounter on its west, then north sides, Court Marshall Lake. In 1778, mapmaker Purcell called it “The Southernmost Great Pond”, obviously unaware of Lakes Merial and White Western. The early 1831 land surveys label it “Bear Pond”. The name Court Martial Lake seems to have originated out of the belief that General Andrew Jackson in his 1818 march across North Florida, executed after a military trial, the British subjects, Alexander Arbuthnot and officer Robert C. Ambrister. The two had been charged with inciting the Indians to war against the United States. Local author and News Herald writer Harold Bell in his book Glimpses of the Panhandle related of a visit to the lake with local resident Ed Banks. On the northwest side of the lake, he describes “an elevated area which is plainly marked out”. He identified this as the campsite of Jackson. Approximately a mile from the site, Bell discovered a corduroy road that he may rightly identify with the Military or Federal Road built in the early 1820’s. It was also the Ekanachattee Trading Path that the Military/Federal Road picked up and used for several miles on its east northeast journey.

There is no documentary evidence that General Jackson ever set foot even near Court Martial Lake. Arbuthnot and Ambrister were tried and executed near St. Marks. Jackson’s march across northwest Florida to Pensacola in 1818 took him much farther north. The closest he ever got to Court Martial Lake was in the Graceville and State Road 2 area, near the Alabama State line.

So the question remains, how did the lake get associated with Andrew Jackson? It is likely that the close proximity of the 1824 Military Road was somehow associated with him. Indeed, the same road in the Gulf Shores and Eglin Air Force Base areas are often referred to as “Jackson’s Trail”. As for the campsite, it is interesting to observe that the distance from the Indian Store at Choctawhatchee to Court Martial Lake is approximately 24.25 miles. This is about the distance that a trading party could travel in a day. The campsite that Banks recollected as being Jackson’s stop, might have been confused with a customary Indian and trader campsite along the Trading Path, and there is indeed an elevated ground on the northwest side of the lake that the Trading Path crosses.

From Court Martial Lake the traveler began a northeasterly ascent into the Sand Hills proper, passing south of Crystal Lake and into present Washington County.

The significance of this trail must first be put in historical context. Before the Revolution, most trade with the Indians filtered through Charleston, but the war disrupted this trade. Pensacola became a major outlet. Goods now flowed from the east to Pensacola. The Chattahoochee/Apalachicola and Choctawhatchee River systems became important highways. One of the routes involved the Indian Store at the mouth of the Choctawhatchee. Maintained by a Mr. Gough, it was probably owned by the Scotsman, John Miler. From the store goods could flow down a natural inland waterway to Pensacola by British schooners and Indian canoes. The overland route to the east would have been along this 100 mile Ekanachattee Trading Path, a segment herein described. The white traders traveled with packhorses that could average about 25 miles per day. These animals proceeded single file, none of them bridled, along the narrow path. Strings of sleigh bells and hawk bells adorned them so that they would not get lost when turned loose at night. European goods that were traded to the Indians consisted of blankets, boots, guns, check shirts, hatchets, calico, gartering, “nonsopretties”, silk ribbon, broad hoes, rum, barley, corn, small beads, bullets, flints, gun powder, looking glasses, thick saddler’s laces, small black duffels, broad ribbons, paint “of which the Red People are very fond”, and knives. From the Indians, the British desired deer skins. So large was this trade that it is said the Indians hunted the deer almost to extinction.

With the coming of the Americans in the 1820’s, settlement patterns changed. Instead of the Indian Store, there was Point Washington. Instead of the Indian village Ekanachattee, there was Marianna and Port Jackson. The trail, though altered, continued in use no doubt through much of the 19th Century. It still survives today as primitive trails and logging roads in many parts of our county.

For more on the history of Bay County, please visit the History Museum of Bay County, 133 Harrison Avenue. Open hours are Tuesday, Thursday and Friday, 10 a.m. to 1 p.m.

Robert Hurst, author of The Spanish Road, Travels along Florida’s Royal Road, El Camino Real. Thespanishtrail.com

Hi, great posts! Just wondering, do you happen to have a copy of the David Holmes journal that you reference here in part one of your post? I would be very interested in reading that. Do you also have larger versions of the images at the end where you’ve traced the path onto your maps around Seminole Hills / Pine Log / Court Martial Lake? It’s a bit difficult to see since the images are small. Thanks!